The categories that naturally come to mind when trying to think up examples of a category (such as sets with functions, groups with homomorphisms, topological spaces with continuous maps, …) are sometimes called concrete categories. These are categories where the objects are sets, usually with some additional structure (group structure, a topology, etc.), and the morphisms are well-defined functions between those sets that preserve the structure. For example, consider Top, the category of topological spaces with continuous maps.

In the case of Top it’s easy to check that the identity map is continuous, that composition of continuous functions yields another continuous function, and function composition in general is associative. With a continuous map, say , we’re taking a point

and assigning it to a single point

(so we have a well-defined function between two sets) in such a way that if we have an open subset

and look at the preimage of each point in

, we get an open set in

. It is in this sense that the structure of the topological space is preserved: preimages of open sets are open sets. In the case of Grp, our morphisms are group homomorphisms, which by their very definition respect the group structure.

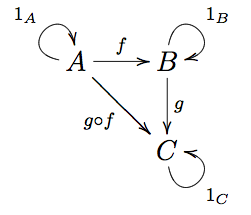

There are, of course, categories which are not concrete. In the last post we saw a very simple category with three objects. These objects aren’t sets, they’re just “things” that we decided to label A, B, and C. The morphisms between these objects aren’t functions in any sense of the word: they don’t associate inputs with outputs, there aren’t even any “inputs” or “outputs” to speak of! Our morphisms are literally just arrows that start at one object and end at another. (For this reason some people simply refer to the morphisms of a category as arrows.)

The above is about as far from a concrete category as you can get, but consider the following example from Awodey. Let the objects of the category be sets. For any sets and

a morphism from

to

is any subset of

(that is, any relation on

and

). The identity relation is taken to be

. For composition of two relations, we say that

is the composition of

and

where

is in the set iff there is a

such that

and

are in the original relations. Here are objects are sets, but the arrows are not functions. The morphisms are collections of ordered pairs

with

and

. This is not a function as we may “associate” one

with several items in

. For example, we may have a morphism

with

.

Leave a comment